A Revolutionary Life

Outside of Italy, Giuseppe Mazzini and his story are not very well known, but he led one of the most interesting and active political lives in Europe at the time. From his middle-class upbringing to organizing dozens of insurrections in Italy to his long-term exile in London, Mazzini merited Aleksandr Herzen's description of him as "the shining star" of Europe's movement for democracy.

Here is his story as best as it can be told, compiled from various sources and works by Risorgimental scholars and historians. I hope it does him justice.

Table of Contents ▼

Early Life (1805-1831)

Giuseppe Mazzini was born in Genoa in 1805. He was born only a few weeks before the city-which had been the capital of the short-lived Ligurian Republic-was annexed by the French Empire and it's moderately liberal constitution can to an end. He was born in his childhood home on the Via Lomellini, which is now the Museum of the Risorgimento in Genoa.

Mazzini was born to his father Giacomo Mazzini, who was a professor of anatomy at the University of Genoa, and to his mother, Maria Draghi, who had been a fervent Jansenist and was the one who had profound moral influence on the young Mazzini. Giacomo, though by the time of his professorship at the university had resigned himself to the French rule, had actively participated in the republic and had supposedly Jacobin leanings.

Mazzini’s house in GenoaMazzini grew up surrounded by two older sisters and was affectionately referred to a "Pippo". He was a sensitive child and developed a love for literature and reading early on in life, and would be influenced by the likes of Dante, Foscolo, Vico, Herder, Goethe, Fichte, Lord Byron, and the Schlegel brothers, and Schelling through his entire life. Mazzini matriculated at the University where his father lectured when he was fourteen years old. He initially began with studying medicine, but switched to law instead when he fainted after witnessing an operation.

At University and Early Activism

While at university, Mazzini’s political awakening began with romantic rebellion. Under the influence of romantic poets and patriotic ideals that he engaged with, Mazzini was a “troublesome scholar” who dissented from the compulsory religious custom observed at the university. He was subversive and fierily eloquent and was admired for “his strength of character, courage and sincerity.” While at university, he joined the secret revolutionary society the Carbonari that aimed to establish a united Italy free from foreign rule under a republic. Mazzini shortly left the secret organization since he disagreed with its secrecy and clandestine methods in bringing about revolution, believing instead that an Italy needed a popular movement brought about by a people’s revolutionary.

In 1829, Mazzini was arrested by the Piedmontese authorities for his activism against the Austrian imperial rule. He had been betrayed by a fellow member and was imprisoned in the fortress of Savona for three months until he was released due to lack of evidence. When released in early 1831, Mazzini chose exile from Italy as a form of punishment, a decision that would affect him for the rest of his life. It was at this point that he truly broke with the Carbonari and began setting up a new organization along his own principles for popular insurrection.

Young Italy (1831-1834)

After being exiled from Italy, Mazzini settled in Marseilles, where he joined other Italian political exiles. He lived in a small room at the house of French sympathizer, Demosthenes Ollivier, and spent most of his time avidly writing pamphlets and preparing papers for distribution.

Flag of Young ItalyYoung Italy was primarily a middle-class movement that advocated for the romantic, patriotic ideal of a united, republican Italy free from foreign oppression. It had a fully constituted membership and a comprehensive political program aimed at achieving Italian unification and implementing a social and economic agenda. Though it was mostly an underground movement due to the repression throughout most of Europe, Mazzini was careful not to follow the secrecy of the Carbonari. For him, the party represented a starting point for creating a common principle of Italian emancipation that would guide true, popular insurrection against the monarchal governments. In his Manifesto of Young Italy, he expressed that:

"Great revolutions are the work of principles rather than of bayonets. They are first achieved in the moral, and then in the material sphere. Bayonets are truly powerful only when they assert or maintain a right. Now, the rights and duties of society spring from a profound moral sense that has taken root in the majority. Blind, brute force may create victors, victims, and martyrs, but the triumph of force always results in tyranny if it is achieved in antagonism to the will of the majority. Only the diffusion and propagation of principles among the peoples makes their right to liberty manifest. By creating the desire and need of liberty, it invests mere force with the vigor and justice of law."

In Hiding

He rarely left the house for fear of being caught by the authorities, but when his frustration with his confinement got overwhelming, he would venture out in disguise. In July 1831, along with a number of other exiles, Mazzini founded Giovine Italia (“Young Italy”) as Italy’s first organized political party.

Young Italy’s founding was a pivotal stage in both Italian political history and in Mazzini’s life. It marked an important step in Il Risorgimento, moving toward both a practical and popular movement toward genuine unification under a moral government. It was at this time that Giuseppe Garibaldi—the revolutionary who would eventually lead the campaigns for a unified Italy—would join the party after meeting Mazzini in Marseilles.

For Mazzini, Young Italy was an opportunity for him to establish a political party based on his moral and philosophical principles. Pertaining to his belief in the harmonization of thought and action, Young Italy was dedicated to two main objectives: education, through propaganda campaigns to promote national consciousness, and insurrection, with planned revolutionary action to try and overthrow the monarchs that governed Italy.

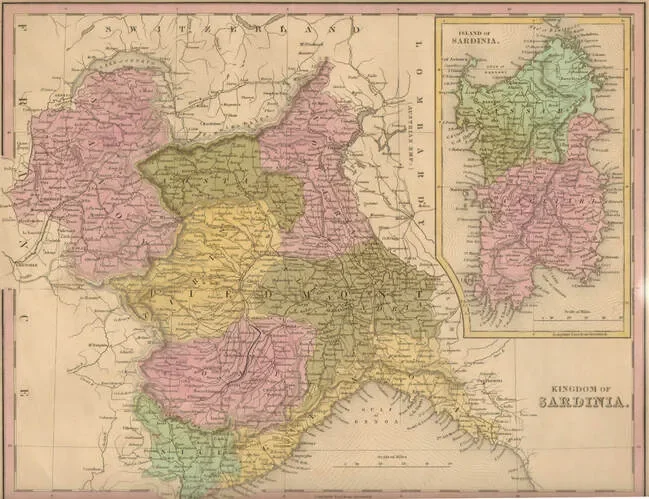

Map of SardiniaFailed Insurrections

From their base in Marseilles, Young Italy launched a number of insurrections against the Italian despotic governments—all of which failed. In 1832, the Naples Plan was meant to bring about a revolution supported also by Tuscan members as well as those in the Papel States. However, the insurrection was forestalled after letters from Mazzini with instructions were intercepted by authorities. In 1833, Young Italy attempted to organize a military coup in Piedmont, however the plot was again discovered, leading to arrests of revolutionaries, including Jacopo Ruffini, a close childhood friend of Mazzini’s, along with others. Ruffini later would commit suicide in prison while being tortured for information, something that would haunt Mazzini for the rest of his life.

In the later winter of 1834, Mazzini organized the ambitious invasion of Savoy (under Piedmontese control), with the help of German and Polish exiles that would hopefully have sparked a wider revolution in Genoa, Naples, and elsewhere. However, this too ended in failure due to the authorities also being forewarned and poor planning, resulting in the expeditionary forces dissolving as soon as it crossed the border. Mazzini also attributed the “fiasco” to the lack of popular support that led to the failure of the wider revolution to materialize.

A Poor Exile (1834-1843)

After the disaster of the invasion of Savoy, as well as his other revolutionary activities, the European governments stepped up their efforts to persecute Mazzini. He was forced to leave France and arrived in Switzerland, which was partially tolerant of him. However, the French, Piedmontese, and Austrian authorities continued to pressure Switzerland for Mazzini’s capture and expulsion, and the Italian revolutionary spent most of his time evading detention, moving from canton to canton.

Political Depression

Mazzini’s time in Switzerland was marked by a period of personal and political crisis. The failure of Young Italy’s insurrectionism had left many who had fought with him disillusioned and deserted him. It was at this point in Mazzini’s life that he faced significant financial hardship and relied on money sent to him by his mother and various business ventures. He suffered from an immense crisis of self-confidence about the possibility of achieving a united Italy, as well as a sincere amount of remorse for the lives lost in his insurrections and their families (including his own). His deep sorrow and depression, suicidal thoughts, his “total desolation of the soul”, suddenly turned to resolve, however, when he realized the selfishness of his own introspection and how he was essentially abandoning his duties. He returned with renewed faith, accepting martyrdom, and ready to take on the world once again.

Young Europe

In April of 1834, Mazzini founded a new political association christened Young Europe. Rather than a mere offshoot of Young Italy, Young Europe was a society made to better internationalize Mazzini’s vision for democratic revolution in Europe. It was made up of several other Young societies from Germany, Switzerland, and Poland, and had members from each country. The goal for Young Europe was to lead a “revolution of nationalities” and to provide a public face to the cause that defined Mazzini’s creed in the nation, stepping even further away from the clandestine Carbonaria. It was to be a “federation of national associations”, affirming "equality among equals”. The association was Mazzini’s first foray into creating a cross-national organization to oppose monarchism and promote his vision of republicanism. The eventual aim of Young Europe was to establish a United States of Europe.

Mazzini in SwitzerlandMazzini’s time in Switzerland came to an end in 1837. After the constant pressure from the surrounding despots, the Swiss authorities finally ordered Mazzini’s expulsion in 1836. Though his reception in Switzerland was mixed, from admirers to detractors (who especially disliked his advocating of ending Swiss neutrality), he finally decided to move to London. His decision wasn’t just the generally more tolerant British attitude toward European political refugees, but also the prospects of financial betterment.

Arrival in London

Mazzini’s arrival in London marked yet another low point in his life. He struggled to find work owing to his poor English and his professed republicanism, and he faced significant financial hardship. He also disliked London for its dirt and noise, and he missed Europe’s peaceful nature. However, he also found himself quickly inducted into the intellectual circles that were made up of political activists from the continent and eventually found himself a job as the English correspondent for Le Monde. By this time, Mazzini had already made important connections to British intellectuals, meeting in 1837 both John Stuart Mill and Thomas Carlyle, living near the latter for a time. In 1838, he returned actively to politics and, despite lacking the proper funding, decided to relaunch Young Italy the following year.

Throughout his first time in London, Mazzini remained very politically active. In 1840, Mazzini published the paper Apostolato Popolare as well as founding the Union of Italian Working Men. He also contributed to the liberal Tait’s Magazine with several articles published in 1839 and 1840. He opened a school for Italian children and refugees who he saw treated appallingly, and taught them literature and history during the evenings. He worked tirelessly towards rebuilding some semblance of his revolutionary activism that he had promoted with both Young Italy and Young Europe, and tried to raise awareness of the plight of Italians.

Mazzini and Marx (1843-1847)

Mazzini’s time in London running up the revolts of 1848 was fraught with both frustration and rivalry. Though his lack of social connections prevented him from actively participating in the political revolutions being planned for Italy, he still contributed toward patriotic efforts through his newspaper and regular submissions to political journals. He began to admire the English systems for their respect for freedom of speech as well as their political system, seeing the quaint localism (as influenced by John Stuart Mill) as a counter to federalist ideas within a unified Italy.

However, despite his moderate exclusion from the conspiratorial movements, Mazzini was still causing the government in Vienna significant headaches. In 1844, the Austrian ambassador in London, Philipp Neumann, requested information from the British government regarding Giuseppe Mazzini and fellow Young Italy revolutionary, Nicola Fabrizi. Lord George Aberdeen, the then foreign minister of the Peel government, in turn asked the Home Office to begin secretly opening Mazzini’s letters, making copies, and reading excerpts to the Austrian ambassador. This was the infamous “Opening Letter Affair”.

The Opening Letter Affair

Mazzini realized that his letters were being opened and compiled, evidence that eventually led to his presenting a petition to Parliament. The scandal caused public upset, and the Italian revolutionary was the object of great sympathy. He was publicly defended by Macaulay, Charles Dickens, Robert Browning, and Lord John Russell, as well as his friend Thomas Carlyle, who called him "a man of nobleness of mind”. The scandal resulted in a debate in Parliament where many MPs condemned the government’s actions. The incident became even more severe when it was reported that two Venetian revolutionaries, Emilio and Attilio Bandiera (the “Bandiera Brothers”) had been captured and executed due to information intercepted in Mazzini’s letters. Mazzini hailed the Brothers as martyrs of the Italian political revolution.

The Opening Letters Affair catapulted Mazzini from obscurity into the British public spotlight. He became much more well-known among British intellectuals and political circles, both on the left and the right. He made the acquaintance of both conservative elites and socialist revolutionaries, becoming much more active in the European democracy movement. He became interested in the Chartist movement and contributed to Julian Harney’s paper The Northern Star, as well as continuing to contribute to the Times and Tait's Edinburgh Magazine. From Harney, Mazzini became closer to the English working class and in understanding the plight of the working class in general.

Indirect Encounters with Marx

It was around this time, particularly in 1846, that Mazzini came up against the communist heavyweights Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Though Marx and Mazzini met through attending similar meetings and associations, the ideological rivalry between the two was stark. Mazzini, though becoming much more socially oriented in his economic policy and his belief in duty, despised communism for its materialist conception of history and the conviction that it would lead to dictatorship. On the other hand, Marx dismissed Mazzini as a “bourgeois ultra-reactionary” and scorned his patriotism as suspicious. Mazzini’s focus on national revolution and a transcendental morality was deeply at odds with Marx’s scientific socialism and class conflict.

In 1846, in the Address to Feargus O'Connor at a meeting of the Fraternal Democrats, Marx and Engels proclaimed that “democracy today is communism” and strongly criticized middle-class liberalism as part of the wider class struggle that held the working classes down. In response—both to distance himself from liberalism and to clarify his own position—Mazzini published a series of articles in the People's Journal that became collectively known as the Thoughts on Democracy in Europe.

Thoughts on Democracy in Europe

In the Thoughts, Mazzini criticized various forms of liberalism and socialism that had dominated the pro-democracy movement during the 19th century. After offering scathing critiques of Benthamism, Fourierism, and Saint-Simonianism, Mazzini turned his pen on communism.

“I have said that communism denied both the individual and society. It does deny both the one and the other, and in their constituent vital elements—liberty, progress, and the moral development of the creature. Wavering between Saint-Simonianism and Fourierism, it borrows from the first one its tyrannical tendencies, its inevitable violation of individual liberty; from the other, its law of satisfaction of the inclinations which it would reduce to wants—in vain, since every strongly felt inclination constitutes a real want to him who feels it: it exceeds them both in its absolute contempt for the past, for all historical tradition, for all manifestation of the previous life of humanity.”

In some ways, as a response to Mazzini’s criticism of communism, Marx and Engels worked on the Communist Manifesto that they published in 1848. Although the Manifesto had the goal of fully developing the communist idea for wider audiences, there were certain points (carefully observed by Salvo Mastellone in his Mazzini and Marx) that were apparently directly at Mazzini’s critiques.

The rivalry between Mazzini and Marx would remain consistent throughout both Mazzini’s time in London, and only increase in their antagonism as the democratic revolts began to engulf Europe during the late 1840s.

The Roman Republic (1848–1849)

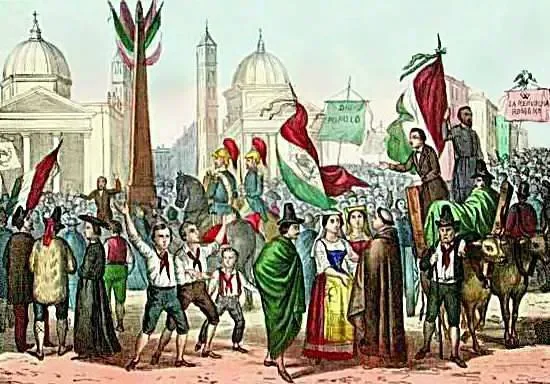

Europe in 1848 saw a wave of democratic, nationalist revolution across the entire continent. Also known as the “Springtime of the Peoples”, a number of revolts broke out against the European autrocratic governments to try and establish liberal, constitutional republics. Prompted by both the industrial recession as well as a food crisis driven by potato blight, liberally minded intellectuals and democratic radicals challenged the conservative that had been established after the Congress of Vienna in 1815.

The revolutions saw some initial successes. The overthrow of the French monarch Louis-Philippe and the establishment of the French Second Republic, as well as the ousting of Austrian Chancellor Klemens von Metternich. The German monarch also conceded several demands to the revolutionaries. However, the revolutions were ultimately put down as monarchs regained power with their militaries that had remained loyal to them. By 1849, the monarchist forces had re-established rule over Germany and Austria.

The Roman Constitution

In 1848, Rome was under the theocratic authority of the Papacy, under Pope Pius IX. In November of the same year, Papal Minister Pellegrino Rossi was assassinated and the Pope fled to Gaeta, leaving Rome in a vaccuum. In his place, a Constituent Assembly was called via election and proclaimed the Roman Republic on February 9th 1849.

The Roman constitution was one of the most progressive documents of its time. It was first constitution in the world to abolish capital punishment and guaranteed complete religious liberty, decisively ending the Pope’s temporal power while upholding his spiritual authority. Beyond these landmark reforms, it enshrined universal male suffrage, equality before the law, freedom of the press, and the separation of church and state. It also emphasized the social role of government, tasking the Republic with improving the moral and material conditions of its citizens and removing barriers to participation in civic life.

Proclamation of the Roman Republic in 1849, in Piazza del Popolo

Mazzini’s Triumvirship

Mazzini arrived in Rome in March 1849, week after Giuseppe Garibaldi had also arrived. He entered the city on foot as an “ordinary pilgrim” and was not initially recognized until after a day of being in Rome. His popularity among revolutionary circles got him elected as a deputy and then was appointed as part of the Triumvirate, along with Carlo Armellini and Aurelio Saffi, although Mazzini was the de facto leader. It was at this point that Mazzini reached his zenith as both a politician and political leader, earning the praise of Russian revolutionary Aleksandr Herzen as "the shining star" of Europe's democracy movement.

During his short time as Triumvir, Mazzini showed great statesmanship and diplomatic skill, showing surprising administrative capacity for governing with wisdom, moderation, and unexpected administrative capacity in difficult circumstances, increasing Italy's reputation in Europe. He protected an enacted political freedoms to an extent largely unequalled elsewhere in Europe at the time, including press freedom, religious freedom, due process, and equality among the sexes.

It was here that Giuseppe Mazzini shone his brightest.

French Military Intervention

In the summer of 1849, the French President Louis Napoleon decided to support the exiled Pope Pius IX in organizing a counterrevolutionary expedition to crush the Roman Republic. The motives for French support of the Papacy were for Napoleon to placate the Catholic faction in France, despite the new constitution prohibiting foreign intervention. In the April of 1849, General Oudinot, leading the French intervention, falsely promised to respect the Roman citizens and so intially met little resistence. However, as the fighting commenced, the French forces were repelled by the passionate defense put up by the republican revolutionaries.

During May and June, there was a brief period of negotiation, where French diplomat Ferdinand De Lesseps was sent to discuss a peaceful resolution with Mazzini. De Lesseps was impressed with Mazzini’s diplomatic skill and the Triumvirate signed a truce at the end of May. However, the French then resumed the attack shortly before the truce was due to end, taking the Republic by surprise.

Giuseppe Garibaldi led the defense of the city, and the republicans put up an admirable fight against the French forces. However, the Republic eventually fell on July 3rd and the Papacy was restoried by the French. Mazzini has resigned his office at the end of June, but refused to sign a surrender, stating: “monarchies may capitulate, republics die and bear their testimony even to martyrdom.” Mazzini managed to escape back to Switzerland, where he spent six months living in secret, but then was eventually expelled again. By the Autumn of 1850, Mazzini was back in London.

In an essay entitled Concerning the Fall of the Roman Republic, Giuseppe Mazzini concluded:

“A population of more than 2 million men, having peacefully, solemnly, and legally chosen a form of government through a regularly elected constitutional assembly, is deprived of it by foreign violence. It is then forced again to submit to the power that had been abolished, and this without the population having furnished the slightest pretext for such violence, or made the slightest attempt against the peace of neighboring countries. The calumnies which for months have been systematically circulated against our republic are of little importance; what matters is that it was necessary to first defame those whom the powers had determined to destroy. But I affirm that the republic, voted for almost unanimously by the assembly, had the general and spontaneous approbation of the country. Of this, the explicit declaration of support by almost all the municipalities of the Roman State, voluntarily renewed at the time of the French invasion and without any initiative on the part of the Roman government, is a decisive proof.”

Back in London (1850–1859)

Mazzini’s return to London after the fall of the Roman Republic was against as a refugee. Though it was yet another failure under his belt, his brief stint as Triumvir filled him with more determination than he had felt in his original time in the English capital. He even saw London in a new light; rather than the depressing, smoggy metropolis that he had disliked so much before, he began to appreciate England as second home. With this new revitalized energy, he set about reorganizing with a refocus on battling out in the European intellectual scene for the heart of the democracy movement in Europe.

Rebuilding the Democratic and International Front

In June 1850, Mazzini founded the European Central Democratic Committee with other revolutionary exiles as a successor to his previous Young Europe. This was a key part of his grander vision for a "Holy Alliance of Nations," a federation of free peoples that would one day become a United States of Europe. In his essays, he articulated the core belief that liberty was indivisible; no single nation could remain free in a continent of tyrannies, making international solidarity and organization essential for survival. He also established Amici d’Italia (Friends of Italy), enrolling 800 members, and a National Italian Committee to help direct revolutionary efforts for republican unification.

His moral stature in Britain soared high, bolstered by the heroic narrative of the Roman Republic's defense. His philosophical views on duty and progress resonated deeply with British radicals. During this time, he also refined his internationalist creed, arguing powerfully that for one people to impose its social solutions on another was an act of "usurpation" that violated the sacred "dogma of collective sovereignty."

More Setbacks

Just as he was rebuilding momentum, the middle of the decade dealt a series of disastrous blows to Mazzini’s cause, plunging him into another period of crisis. The attempted insurrection in Milan in February 1853 was a particularly crippling failure, a devastating echo of the fiascos of the 1830s.

Poorly planned and quickly crushed, it not only shattered his clandestine networks within Italy but also badly damaged his standing in Britain, where critics began to view him as a reckless agitator. Following other unsuccessful ventures in Carrara and Valtellina, Mazzini’s strategic focus shifted. He increasingly saw the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia not as a potential ally, but as a rival, and identified the agrarian, oppressed South as the crucial theater for sparking a genuine, popular uprising.

Returning to London in late 1854 after a brief stay in Zurich, his anxiety grew as he perceived the looming threat of a French protectorate in Tuscany. He believed the only way to forestall foreign domination was for the national party to seize the initiative with immediate, decisive action in Naples and Sicily. His frustration with the cautious, diplomatic approach of Piedmont, led by Cavour, boiled over. By October 1854, he bitterly labeled the kingdom "our curse."

He contended that its superficial liberties—a limited franchise and a controlled press—and its ministers' vague promises of foreign support were a slow poison, luring patriotic Italians into a state of passive patience. This strategy, he argued, was designed to sideline popular will and ensure that any unification would be a top-down conquest by the monarchy, not a bottom-up liberation by the people. His opposition was further cemented when he vehemently condemned Savoy's alliance with its traditional enemy, Austria, regarding the Crimean War—a move he saw as the ultimate betrayal of the national cause for political expediency.

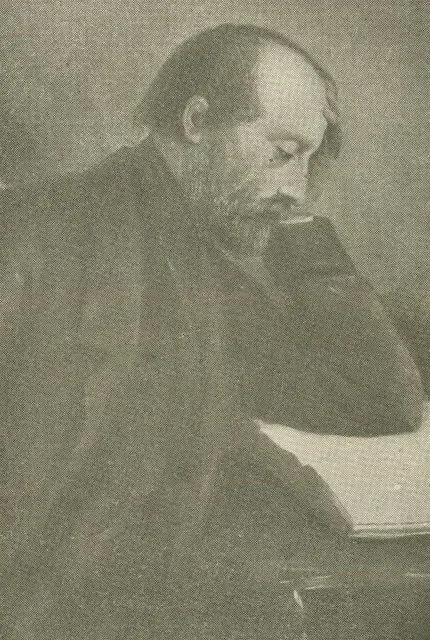

The Rise of Count Cavour

Born into the Piedmontese aristocracy, Count Camillo Benso di Cavour was a worldly and ambitious statesman whose pragmatic approach to politics was entirely alien to Mazzini's moralistic idealism. Their relationship quickly became one of the defining rivalries of the Risorgimento, a clash of personalities, ideologies, and strategies for achieving a unified Italy. Where Mazzini dreamed of a popular, democratic uprising creating a republic from the ground up, Cavour envisioned a unified Italy under the constitutional monarchy of King Victor Emmanuel II, achieved through shrewd alliances and calculated warfare: a top-down expansion of Piedmontese power.

This ideological chasm bred intense personal animosity; Cavour openly labeled Mazzini the "Chief of the Assassins," while Mazzini, seeing Cavour's pragmatism as a moral failing, derided him as a "second-hand Machiavelli" whose reliance on foreign powers was an "anti-national" betrayal.

Throughout the 1850s, as his own star rose, Cavour waged a relentless campaign to suppress and discredit his rival while paradoxically exploiting the very threat Mazzini represented. He imprisoned Mazzini's followers without trial, shut down sympathetic newspapers, and orchestrated a propaganda war that painted the revolutionary as a vulgar assassin and a communist.

Camillo Benso, Count of CavourNonetheless, Cavour skillfully used the specter of Mazzinian revolution as a diplomatic tool, warning Napoleon III that only a successful, Piedmont-led war against Austria could eradicate Mazzini's "malign influence" and stabilize Italy. He capitalized on the failures of Mazzinian insurrections, like the Milan uprising of 1853, to repress the republicans while simultaneously scoring diplomatic points against Austria.

Even as many patriots, swayed by pragmatism, defected from Mazzini's cause to Cavour's, the Count was often frustrated by the exiled revolutionary, who, from his shabby London lodgings, somehow obtained remarkably accurate intelligence on Cavour's secret diplomatic agreements. Ultimately, Cavour's vision prevailed, but many observed that in his successful unification of Italy, he had been "compelled into appropriating so much of Mazzini's programme," a testament to the enduring power of the ideas he fought so hard to defeat.

Final Insurrections

Facing repeated military failures and the rising political influence of Piedmont, Mazzini shifted his focus in the latter half of the decade. Though he never abandoned the cause of insurrection, he increasingly wielded the power of ideas as his primary weapon, determined to maintain ideological purity and keep the spirit of a truly popular revolution alive. After secretly returning to Genoa in 1856 to organize, his movement saw its last serious insurrectionary attempt with the Sapri Expedition in 1857.

Led by his disciple Carlo Pisacane, the expedition to incite a revolt in the South failed tragically, ending in Pisacane's death. Yet, its martyrdom renewed the possibility of a "democratic-populist alternative" to a monarchical takeover, a potent threat that spurred Victor Emmanuel II's government to accelerate its own diplomatic and military plans for unification. In the aftermath, Mazzini, though he narrowly evaded capture, was condemned to death in absentia, cementing his status as the arch-enemy of the established Italian states.

Developing His Political Thought

From the safety of London, he launched the paper Pensiero e azione ("Thought and Action") in 1858. This journal became his platform to champion emergent European nationalities—Poles, Hungarians, and Slavs—and to reiterate his core beliefs to a new generation. "We are against monarchy not because we are republicans," he wrote, clarifying his position, "but because we believe in unification"—a true, moral unification that monarchy, in his view, could never achieve.

It was here he also published parts of his seminal work, On the Duties of Man, a profound critique of the era's focus on individual rights. He argued that a society built on rights alone would lead to egoism and conflict; true progress could only come from fulfilling one's duties to humanity, family, and country. In 1859, this principled stand put him in vehement opposition to the alliance between Piedmont and Napoleonic France, a pact he viewed as a cynical betrayal of national self-determination that invited foreign domination.

Yet, when war came, Mazzini’s ultimate priority remained a unified Italy. In a painful but pragmatic compromise, he pledged his conditional support to the king, urging him to rely on popular volunteer forces rather than French armies, so that the nation might be built on the "three inseparable bases of unity, liberty, and independence."

Final Years (1860–1872)

The proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy in 1861 was not a triumph for Giuseppe Mazzini, but a profound disappointment. He saw the new state, forged by Cavour's diplomacy and royal armies, as a soulless "annexation" of territories, spiritually deficient and lacking the moral regeneration he believed could only come from a popular, republican uprising. Despite this, he refused to abandon his role as the nation's conscience, seeing himself as the "spur" needed to drive unification to its true completion by acquiring Venice and Rome.

Back in London, battling declining health, he reluctantly oversaw the publication of his collected essays, a project that brought him much-needed income and a chance to remind a new generation of the republican ideals the monarchy sought to erase. His resolve was only hardened by the defection of former followers like Francesco Crispi, who embraced the monarchy, an act Mazzini condemned as pure opportunism.

Increasing Isolation

As the years passed, Mazzini found himself increasingly isolated, a man out of time. He was an enemy of the new monarchical state yet found no home in the emerging radical left. In 1866, voters in Messina elected him to the Italian Chamber of Deputies, but after the monarchy annulled the results twice due to his standing death sentence, he won a third time only to refuse the seat, unwilling to swear an oath of loyalty to the King. His political world shrank further after the disastrous defeat of Garibaldi's volunteers at Mentana in 1867, which caused an "irreparable" breach between the two old revolutionaries.

Simultaneously, the rise of the socialist International, led by figures like Mikhail Bakunin, made Mazzini's focus on national duty and class collaboration seem antiquated to a younger generation of radicals, rendering him, in their eyes, "out of date and out of touch." Ever the conspirator, he planned one last revolutionary gamble, traveling secretly to Sicily in 1870 to incite a rebellion to seize Rome, but he was arrested upon his arrival in Palermo and imprisoned in the fortress of Gaeta.

Final Campaign

Mazzini was freed by a general amnesty after Italian troops finally captured Rome in October 1870, the event he had dreamed of for decades. Yet, he could take no joy in its monarchical context. Returning to London and then Switzerland, he cemented his final break with the European left by issuing a fierce condemnation of the Paris Commune in 1871.

He saw its revolutionary socialism as a "terrible threat" to his vision of a united society built on peaceful class collaboration, a stance that led Karl Marx to dismiss him as a reactionary. Refusing to visit the new capital he felt had been stolen from the people, he spent his last year campaigning through his final newspaper, La Roma del Popolo (The Rome of the People), continuing his fight for a republican Italy from afar.

Mazzini dying of pleurisy at 66Mazzini’s Tomb in GenoaDeath

Unwilling to accept the royal amnesty that would have required him to recognize the monarchy, Mazzini lived his final year in a state of "paradoxical internal exile." Under a false name, he resided in Pisa, a fugitive in the very nation he had willed into existence. There, on March 10, 1872, he died of pleurisy at the age of 66. His body was carried in a grand procession to his hometown of Genoa, where a funeral attended by some 100,000 people mourned the passing of the Soul of Italy.

His tomb can be visited for free at the Cimitero monumentale di Staglieno in Genoa.

“La vita mi pesa, ma credo sia debito di ciascun uomo di non gettarla, se non virilmente o in modo che rechi testimonianza della propria credenza.”

“Life weighs heavily on me, but I believe it is every man’s duty not to throw it away, except manfully or in such a way as to bear witness to his own belief.”