Home / Who was Giuseppe Mazzini? / Who’s a Mazzinian?

Hello, World!

Legacy: Who’s a Mazzinian?

Giuseppe Mazzini had an idiosyncratic, if not erratic, political belief system. It has been often commented on in books about his political thought that, although there was certainly a strong moral dimension, the systematic strength to his ideas was not very clear. Indeed, this really came from the thinker himself, who, as a religious Romantic, disliked immensely the systematization of both history and politics beyond the Christian faith. In fact, the philosophical base for most of his thought comes from his unshaken belief, rather than a carefully organized body of thought like Marxism or liberalism.

However, even though it has never been a historical school, there have been clear examples of Mazzinians throughout history, even before Mazzini came about. Even with a lack of direct influence, there are characters throughout political history that resemble similar ideas that follow the same lines as combining the democratic and nationality principles into one idea, and despite noticeable differences, there is, at least in spirit, a form of Mazzinianism that transcends the man and echoes across time.

Table of Contents ▼

Who’s a Mazzinian?

Labelling someone as a Mazzinian is a tricky business since there were very few (especially outside of Italy) who would have called themselves that. Defining a Mazzinian then is not a case of finding direct or even indirect influence from Giuseppe Mazzini, but instead by observing certain patterns in their political beliefs and actions that share similarties to Mazzini’s unique mix.

This is not just simply finding someone who is patriotic and committed to liberal values since this can be attributed to many different movements and people. For instance, the Spanish political party Ciudadanos could be described as both, but it is not a Mazzinian party since it doesn’t combine these in the right Mazzinian way.

What Are the Key Mazzinian Traits?

At their core, a Mazzinian is someone who effectively and necessarily combines the principle of democracy through the context of national expression. In other words, a Mazzinian will, in some way, believe that freedom and popular government and the consolidation of the nation as both one and the same. There may be variations of both democracy and nationhood to consider in terms of definition, but ultimately a Mazzinian will believe that both are necessary for the other to exist.

This principles leads to the fundamental Mazzinian principle of the harmonization of individuality and association. Unlike other doctrines based on nationalism or communism or liberalism, Mazzinians are unique in that take both as sacred and make work together effectively.

Along with that basic principle, there are a number of other traits that many Mazzinians share:

Duties & Rights: For Mazzinians, a just government and society are founded on the essential principles of both duties and rights. However, they place special emphasis on duties, which, according to Mazzini, are more timeless and fundamental than rights. Unlike rights, which are often legally defined by a constitution, duties are derived from abstract reasoning rooted in either a divine framework or philosophical thought.

Republicanism: Republicanism was a core part of Mazzini’s belief system. He was strongly anti-monarchical and was suspicious of the possibility of a constitutional monarchy. However, though the vast majority of Mazzinians identified here were republicans (popular government elected by the people), for a true republican society to function, it needs commitment to civic values which, in our modern context, could well be found in governments with parliamentary monarchies.

Mixed Economics: In many ways, Mazzini was an early social democrat and envisioned a form of economics that was neither laissez-faire nor socialist. A Mazzinian will tend to combine their economics with the two principles of individual innovation and macroeconomic stability. This means the Mazzinians will tend to follow Keynesian or Georgist principles of economics, but with a strong belief in the free market to allow for individual emancipation. The Mazzinian often emphasizes class collaboration rather than warfare narratives.

Internationalism: What sets Mazzinians apart from nationalists is their international orientation. Rather than a solipsistic commitment to their country and their country alone, the Mazzinian believes that all nationalities ought to be free in the same way. A Mazzinian therefore often believes in international solidarity and it is our role to defend our principles universally. In terms of expression, the Mazzinian could oscillate between humanitarian interventionism and democratic realism.

Possible Mazzinians

As stated above, there has never been a school of thought called Mazzinianism at any point in history. Given the unorthodox nature of Mazzini’s thought and his general failure in creating a revolutionary movement around his ideas, the idea of a Mazzinian in any standard sense is ahistorical.

That being said, the spirit of Mazzinianism has been represented by numerous characters of history in the past. Some have either been directly or indirectly influenced by the Italian revolutionary, or have come to the same conclusions through pure coincidence. The commonality between these political actors is that combined democratic republicanism with a belief that the nation is that connecting bridge between the individual and humanity.

Here is a list of the possible Mazzinians that history has offered:

Sun Yat-sen

Sun Yat-sen (1866–1925), Chinese revolutionary and founder of the Chinese Republic, was perhaps the best representative of Mazzinianism in its original and most practical form.

Sun was directly influenced by Giuseppe Mazzini’s democratic republicanism and political philosophy, and adapted them into the Chinese context with his Three Principles of the People. These principles sought to create nationalism, democracy, and the welfare of the people in a modern China.

Sun represented much of the foundations of a practical Mazzinianism in terms of constitutional organization and economics. As a Georgist, Sun’s economic ideas were oriented in a way that allowed for fairer taxation and land distribution in line with similar aspects of Mazzini’s social democratic goals. His vision included not only political reform but also social and economic improvements aimed at benefiting the masses, reflecting Mazzini’s ideals of popular democracy and social responsibility.

With his political party, the Kuomintang (KMT), Sun Yat-sen led the original revolution against the Qing dynasty to found the Republic of China in 1911, serving as its first president. However, faced with political realities and powerful opposition, Sun resigned the presidency in early 1912 in favor of Yuan Shikai, believing this move was necessary to secure the abdication of the Qing emperor and to ensure a peaceful transition to republican government.

After his resignation, Sun remained dedicated to the revolutionary cause and continued to pursue efforts for constitutional government, social reform, and national reunification. Though he faced setbacks and periods of exile, his faith and vision inspired future leaders and shaped the trajectory of modern China. Through Sun, Mazzini’s ideals found a living expression adapted to the Chinese struggle for democracy and nationalism.

Mahatma Gandhi

Mahatma Gandhi (1869–1948), the leader of India’s independence movement, represents a unique and strategic adaptation of Mazzinian thought.

While Mazzini was already an admired figure in Indian nationalist circles, Gandhi engaged with his democratic ideology by selectively reinterpreting it to align with his own doctrines of ahimsa (non-violence) and swaraj (self-rule). Gandhi appropriated Mazzini’s core ideas not just as a model for a nation-state, but as a philosophical foundation for a distinctly Indian path to freedom.

Gandhi reworked Mazzini’s principle of duty for his own concept of swaraj, which he defined as the individual’s duty to “learn to rule oneself.” For Gandhi, this inner discipline was the essential precondition for outer political freedom. Like Mazzini, he asserted the primacy of duty over modern theories of individual rights, arguing that rights without corresponding responsibilities failed to unite a nation and foster the spiritual bonds necessary for true independence.

During the struggle for India’s independence, Gandhi’s interpretation of Mazzini served as a powerful counter-narrative to more extremist Indian nationalists who cited the Italian revolutionary to justify political violence. He presented Italy’s unification as a cautionary tale, arguing that its reliance on violence had failed to achieve Mazzini’s vision of true spiritual and popular freedom, leaving the nation in a state of "slavery." Through this strategic reinterpretation, Gandhi effectively neutralized the violent use of Mazzini’s legacy in India and established an alternative, non-violent Mazzinian "truth" for the independence movement.

Carlo Rosselli

Carlo Rosselli (1899–1937) was an Italian socialist and antifascist resister during Mussolini’s dictatorship. Born to a Jewish family in Rome, he was influenced by Mazzinian principles from an early age as members of Rosselli's paternal family, the Rosselli-Nathans, were “close collaborators of Giuseppe Mazzini” during his long exile in London.

For Rosselli, Mazzini was an important symbol for republican and patriotic values, despite his concerns about the potential authoritarianism in some of Mazzini’s writings:

Rosselli carried his Mazzinianism as a source of moral fervertude in his activism against the Fascist State. He founded the antifascist group Giustizia e Libertà (Justice and Liberty) along with his brother, Nello, and both fought on the Republican side during the Spanish Civil War.

Rosselli was the author of the revisionist socialist book Liberal Socialism which challenged Marxist historical materialism and sought to fundamentally redefine the socialist project. He argued that socialism should be understood not as a scientific certainty dictated by economic laws, but as a moral ideal rooted in the principle of political liberty. This critique stemmed from a desire to provide the socialist movement with a new, voluntaristic perspective, believing that Marxism's deterministic and materialist framework was politically fatal in the face of rising Fascism because it failed to account for human will and ethical motivation.

His thought was also deeply shaped by his observations of the British Labour Party, which he saw as a practical example of a successful, non-Marxist socialist movement that valued gradual reform and operated firmly within a democratic, liberal tradition.

“I believe that all social and political movements can benefit from the moral teaching underpin-ning the thought and action of Mazzini, but it must be remembered that the more modern, efficient forms of Republican propaganda all stem from Cattaneo, not Mazzini.”

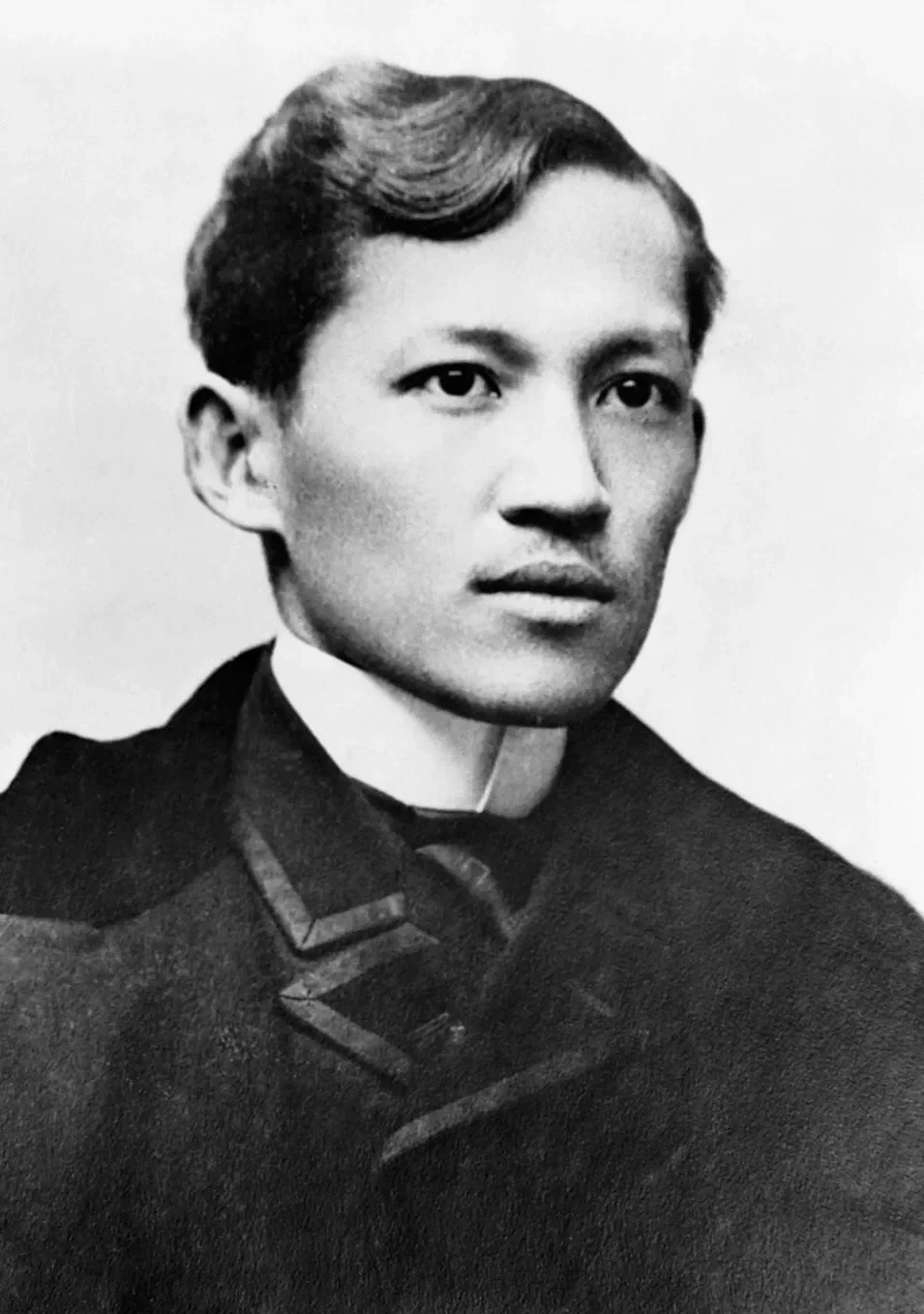

José Rizal

José Rizal (1861–1896) was a Filipino nationalist, intellectual, and anti-colonial activist during Spain’s colonial rule. Born to an educated mestizo family in Calamba, Laguna, he was influenced by liberal and patriotic principles from an early age, as members of his family, particularly his brother Paciano, were connected to the burgeoning nationalist sentiments and the reformist priests who were executed in 1872.

Rizal was influenced by Mazzini during his travels in Europe, particularly by his republican and patriotic values, despite his concerns about the potential for chaos and tyranny in unprepared, violent revolutions.

Rizal was the author of the transformative nationalist novels, Noli Me Tángere and El filibusterismo, which challenged the moral and political foundations of Spanish colonialism and sought to fundamentally define the Filipino national project. He argued that national liberation should be understood not as a simple transfer of power dictated by revolutionary force, but as a moral ideal rooted in the principles of education, civic virtue, and national consciousness. This critique stemmed from a desire to provide the nationalist movement with a new, evolutionary perspective, believing that a violent uprising without an enlightened populace was politically fatal because it failed to account for the ethical and intellectual foundations necessary for true independence.

His thought was also deeply shaped by his observations of Europe during his travels. He saw the political and social progress in countries like Germany, Britain, and France as a practical example of how liberalism, scientific advancement, and a strong national identity could lead to prosperity. He viewed this as a successful, non-violent path to progress that valued gradual reform and operated firmly within a tradition of intellectual and moral enlightenment.

Francisco Morazán

Morazán (1792–1842) was a Central American general and statesman who led the Federal Republic of Central America before it disintergrated in 1839.

Despite being born earlier than Mazzini and that there was no direct contact between them, Morazán embodied the fundamental Mazzinian ideals of belief in nation and in civic duty, despite his passionate federalism that Mazzini opposed.

Morazán’s more crucial political ideas came out of his Manifesto of David, which he published in 1841. He passionately defended democratic republicanism by championing the core values of liberty, justice, and independence.

He condemned tyranny, political corruption, and religious fanaticism, while clearly expressing his support for the rule of law through concrete liberal measures such as freedom of the press and habeas corpus. At the same time, he vehemently rejected any form of absolute government or monarchy. Ultimately, Morazán framed the conflict as a moral struggle, asserting that the true Central American homeland belonged solely to those willing to fight for its freedom and democratic principles.

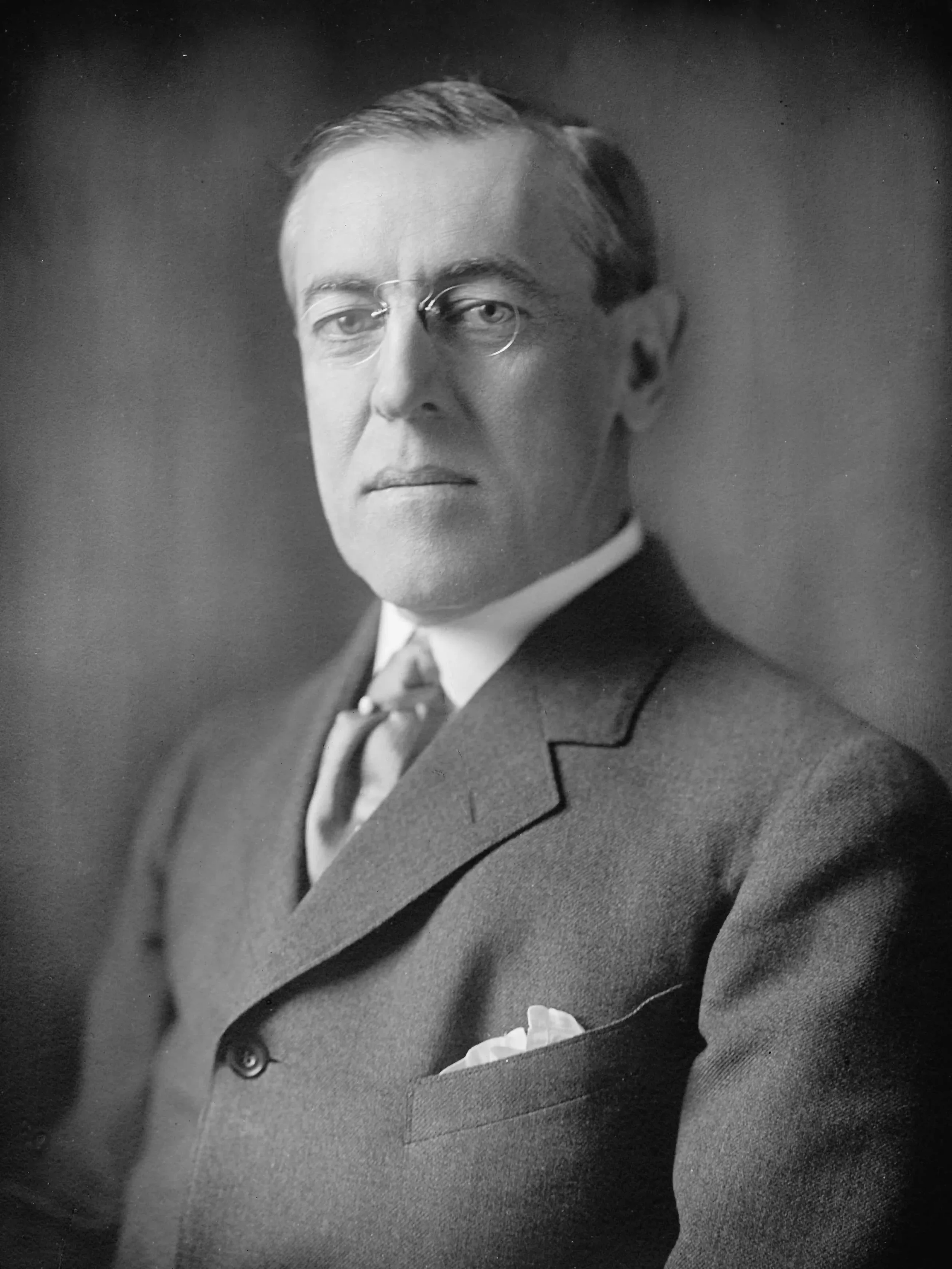

Woodrow Wilson

Woodrow Wilson (1856–1924) was perhaps the one who brought some of Mazzini’s most forward thinking ideas into reality. The 28th US President commented on Mazzini many times in his writing and even went to visit his tomb in Genoa on his way to the Paris Peace Conference in 1919.

Mazzini’s writing on early liberal internationalism deeply influenced on Wilson and his foreign policy. Wilson’s support for self-determination of small peoples and democracy were directly derived from Mazzini’s own ambitions for international peace. Of course, much of this was undermined by his appeasement and promotion of US racialism and the US’s appalling treatment of Haiti from 1915 onwards.

This was particularly clear in the idea of the League of Nations. Mazzini was regarded as the "father of the idea of the League of Nations" and David Lloyd George, another architect of the Versailles settlement, also recognized this, stating that the map of Europe after the war was the map of Mazzini, who taught not only the rights of a nation but also the rights of other nations.

Mazzinian Philosophers

Since the philosophical basis for Mazzinianism is derived predominantly from Mazzini’s own deeply held Christian faith, there have been no true philosophers who explicitly identify as Mazzinian.

However, there are clear and notable examples throughout history that provide a significant foundation, which helped shape and eventually lead to the development of his thought. These philosophers, drawn from various periods and traditions, span across history and offer important insights that resonate with the core principles found in Mazzini’s political thought.

Cicero

Mazzini and Cicero have a lot in common with their individual political philosophies. They both shared conviction that morality and civic obligation are the bedrock of a just society. Both thinkers prioritized duty over individual rights, a concept central to Cicero's De Officiis, arguing that a focus on obligation, rather than entitlement, fosters the self-sacrifice necessary for a virtuous state.

Both championed a moralized form of politics, believing that public life must be guided by ethical principles and that leaders should embody virtue. This ideal found its ultimate expression in their mutual advocacy for a republican government, which they viewed not merely as a political structure but as a moral enterprise essential for liberty and collective endeavor.

Immanuel Kant

Kant's influence on Mazzini was significant on his universalization of rights and democratic peace, despite a lack of direct textual engagement between the two thinkers. Both envisioned a cosmopolitan future where autonomous, republican nations could coexist peacefully, anticipating the core tenets of democratic peace theory.

A striking parallel emerges between Mazzini's call for national will to be restrained by a universal "law of Humanity" and the logic of Kant's categorical imperative, reflecting a shared foundation in universal moral duty. However, their paths diverged sharply on methodology; where Kant proposed a non-interventionist, regulative ideal for perpetual peace to be achieved gradually, Mazzini advocated for an activist, even revolutionary, approach. He believed peace was a political goal to be actively secured through peoples' direct action and just wars for national self-determination, a stark contrast to Kant's more cautious, legally-grounded framework.

Johann Gottfried von Herder

The influence of Johann Gottfried Herder on Mazzini's thought is foundational, yet Mazzini fundamentally transformed Herder's cultural concepts into a potent political doctrine. He embraced Herder’s core idea that every nation possesses a unique mission, an idea rooted in Herder’s concept of Volkgeist—the national spirit expressed through a people’s shared language, folklore, and traditions. For Herder, this linguistic and cultural identity was the pre-political essence of a nation, an organic phenomenon to be respected within a pluralistic cosmopolitanism. Mazzini, however, radically politicized this notion.

While Herder focused on preserving the nation's cultural soul, Mazzini seized upon these elements as mere "indications" that demanded political expression. For him, a nation was not just a cultural body but an active political association of equals that required a sovereign, republican state to fulfill its God-given mission. In doing so, Mazzini repurposed Herder's organic, cultural framework into an urgent, future-oriented revolutionary project aimed at establishing democratic legitimacy.

Simone Weil

While Simone Weil never engaged with Mazzini’s thoughts, her emphasis on the need for roots and on duties in the context of the nation was very Mazzinian in style. The most striking parallel lies in their shared prioritization of duty over rights; just as Mazzini's The Duties of Man rejected liberal rights discourse in favor of sacrifice and collective obligation, Weil's The Need for Roots was framed as a "Prelude to a Declaration of Duties towards Mankind."

Both also infused politics with a profound spiritual dimension, with Mazzini's "religion of the nation" mirroring Weil's deeply spiritual and Christian-rooted approach to social justice. Furthermore, Mazzini's concept of "association"—the need for individuals to unite in democratically governed nations—finds a powerful conceptual echo in Weil’s central thesis on the human need for "roots" within a community to avoid spiritual and social uprootedness. As critics of the dominant ideologies of their eras, both sought a more morally grounded path for society, one founded on obligation and spiritual purpose rather than materialism or pure individualism.

Who Is Not a Mazzinian?

Consequently, there are many people in history who have either used Mazzini’s name to justify their ideology or could be confused for Mazzinians who actually aren’t. Here’s a list of those who do not fullfill the Mazzinian definition.

Giovanni Gentile

Despite calling himself a Mazzinian and using Mazzini’s principle of thought and action to justify his philosophical conception of Fascism, Gentile cannot be considered a Mazzinian in any way. His justification for absolutist statism had nothing to do with the principle of democratic nationality and his appeal to country was merely as window dressing to make his totalitarian ideology more pallitable. Gentile himself regarded Fascism as distinct from the liberal Italian nationalism and Mazzini would have likely regarded Fascism as a terrible form of recrudescent monarchism.

Otto von Bismarck

Germany and Italy were unified in the same year (1871), though taking different routes. Mazzini, who was of course alive at the time, was harshly critical of Bismarck’s methods for achieving German unification and disapproved of his cold pragmatism. However, Bismarck did have some Mazzinian traits, particularly in his later years as Chancellor in regards to economics, but ultimately his more pragmatic style ran counter to the principled conception of Mazzinian duty.

Benjamin Disraeli

One-Nation Toryism has some of the typical traits shared by Mazzinians. Mixed economics aimed at class collaboration through the context of national unity, but ultimately Disraeli moves toward a more socially-oriented form of conservatism was mostly paternalistic in nature, rather than revolutionary or republican.

Simón Bolívar

Simon Bolívar had many of the typical Mazzinian traits in his revolutionary resistence against the Spanish Empire. He was pro-republican and believed in cultivating civic virtue through education, but ultimately he represented a belief in liberal republicanism rather than the spiritual concept of democratic nationality.

Modern Populism / Vulgarism

The modern movements of populism in Europe, the US and elsewhere had some of the typical Mazzinian elements of national expression, but little else. The lack of any comprehensive philosophical framework or vision has left a gaping hold that has been filled by vulgarism. Vulgarism, such as represented in Trump, Salvini, Bolsonaro, and others, is even less Mazzinian.