Tikvah Universalit

Perhaps the most spiritual and romantic of all national anthems, and indeed of all music in general, is Hatikvah. The Israeli national hymn was originally composed as a seven-stanza poem by Naftali Herz Imber in 1878. It was adopted at the anthem of the Zionist Movement at their first congress in 1897, and the abridged version is the Israeli national anthem. If you ever have a spare moment to dedicate time to some spiritual uplifting and linguistic development, I would try to study the abridged version in the original Hebrew in order to get the true essence of what this beautiful song tries to convey.

But I my commentary on Hatikvah “The Hope” is not merely one of a subjective review of all the national anthem in the world (since it is my sincere view that my nation of Britain should deeply consider changing ours), rather it is to introduce an important point on the development of democratic nationalism as both a political and spiritual movement, and its remarkable influence taken from the history, culture and ideas from the Hebrew nation. The relationship between Zionism and democratic nationalism, although pure accidental upon discovery, was not I believe and accident in design.

My Jewish Connection

I am not Jewish, culturally, ethnically or religiously. When I was nineteen, I discovered a rumour that on my mother’s side of the family, we had Jewish ancestry, that my great-great grandmother had been Jewish and that we must have had significant Jewish heritage. I was quite taken with this idea, having previously paid not close attention to my heritage (it was an arbitrary and materialistic concept to me that bore no relevance to who I am). Yet, the possibility that I was in some way related to “that gifted people” was quite impressionable on my personal development. I was so convinced.

I carried this idea with me into investigating my family tree and devoting a large portion of my brief time at university into learning Hebrew and Jewish, Israeli culture. I was fascinated to say the least. Three years later, I had made no real progress in researching my heritage until I met an Israeli. Instantly my interest in Jewishness reopened and I decided to do a DNA test, the results of which, to me, were disappointing. However, my attraction to Israel and Judaism has remained, and I have become more influenced than ever by its deep spiritual power. There is a longing within me still of a desperate desire to join the Jewish people and to share their history and culture. It’s an odd feeling for someone so completely unattached, but it’s present none the less.

Hatikvah and Its Romance

I return again to Hatikvah:

כֹּל עוֹד בַּלֵּבָב פְּנִימָה

נֶפֶשׁ יְהוּדִי הוֹמִיָּה,

וּלְפַאֲתֵי מִזְרָח קָדִימָה

עַיִן לְצִיּוֹן צוֹפִיָּה

עוֹד לֹא אָבְדָה תִּקְוָתֵנוּ

הַתִּקְוָה בַּת שְׁנוֹת אַלְפַּיִם

לִהְיוֹת עַם חָפְשִׁי בְּאַרְצֵנוּ

אֶרֶץ צִיּוֹן וִירוּשָׁלַיִם

As long as in the heart, within,

A Jewish soul still yearns,

And onward, towards the ends of the east,

An eye still looks toward Zion.

Our hope is not yet lost,

The hope of two thousand years,

To be a free people in our land,

The land of Zion and Jerusalem.

I don’t believe there exists a more solemn and deeply holistic composition than Hatikvah. The romantic elegance and intense beauty has such incredible power that it quite often moves me to tears, despite its audience being the Jewish nation. It is partly this poem, and partly the works of the Hebrew essayist Ahad Ha’am, that reveals the universal applicability of Zionism to the democratic nationalist movement. I see a likeness in this applicability in the relationship between Judaism and Christianity. In more ways than none, the ideas of the Jewish nation and the personal relationship with God were exported through the Resurrection of Christ; Christianity, vastly simplified, became an exportable version of the Jewish faith. There is a similar connection, however anachronical, between that of spiritual Zionism and democratic nationalism.

The romantic yearning for national self-determination is eloquently illustrated in Hatikvah. “A Jewish soul yearns”, a reference to the Hebrew people’s natural and unending longing to return to the land of Zion and become once again a Hebrew people, is a sentiment matched by other nationalist movements. נפש יהודי “the Jewish Spirit” captures accurately the spiritual attachment to the sense of the nation. It is a spiritual yearning to part of your nation (with or without a state), and that is only expressed through a romantic means. The Jewishness of the spirit reference is a call to the Hebrew nation, but this can be taken as representational as a natural call for all nations. The universalism is further explored in the last verse להיות עם חופשי בארצנו or “to be a free people in our land”. This again is a universal desire of all people’s. Hatikvah therefore, unconsciously of course, projects an archetype. The Hebrew people, Judaism and spiritual Zionism, integrated together, therefore can be considered as a real world archetype of the ultimate struggle of a people.

Tale of Two Zionisms

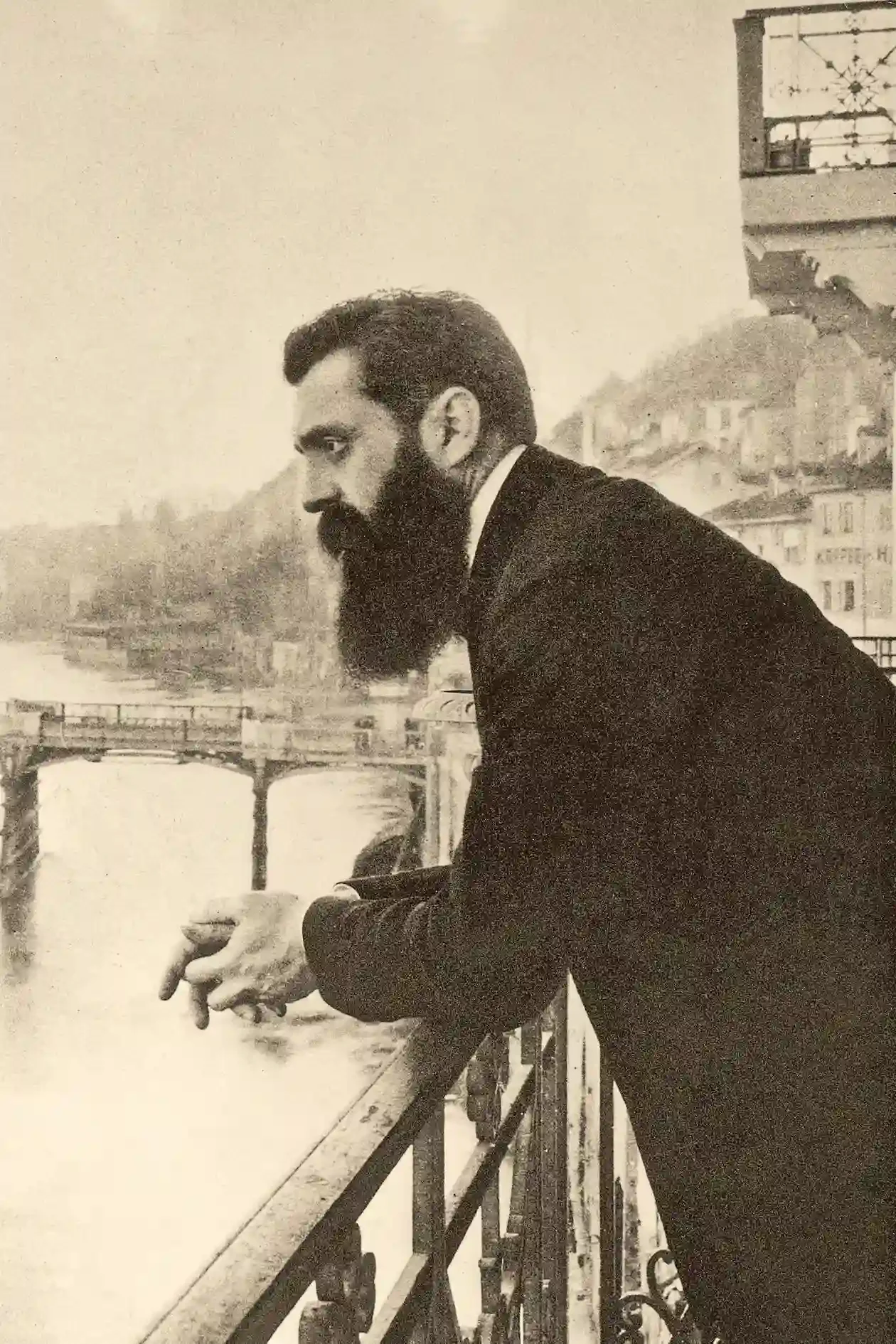

I would like to turn then to the question and relationship of spiritual Zionism and the ideas of (my strain at least) democratic nationalism. For this, it is important to introduce a character of the early Zionist movement whose essays have deeply moved me. Many see Theodor Herzl as the founding father of Zionism. Indeed, Herzl is rightly regarded as promoting the Zionist movement as the president of the Zionist Organisation and for attempting to get political support from governments around the world for the idea that the Jews should have a state of their own. Herzl’s two books, Der Judenstaat and Altneuland brought the idea of political and practical Zionism to the forefront of debate in the Jewish community.

Theodore Herzl תאודור הרצל

My overall criticism of Herzl from reading Der Judenstaat is two-fold. Firstly, his tone throughout the pamphlet is neither romantic or aspiring, but fiery and angry. His (rightful) hatred of anti-Semitism and the treatment of the Jews throughout Europe is expressed more than his intentions to form a Jewish nation. What seems to be clear to me is that the argument he presents in favour of a Jewish State is less from a will to resurrect the Hebrew nation and more a practical method for removing the Jews from harm’s way in Europe; a desperate resolution of the Jewish question to save the Jews from worse. However, noble as maybe these intentions were and from a wish to avoid utopianism, Herzl indeed made no consideration for what it is to be a nation. Herzl’s Israel would have merely been a state of Jews as a refuge from persecution who immigrated to the land without a single language or culture. It would have become something of a Jewish Switzerland in the Middle East with German as the official language.

Herzl’s practical Zionism (or ציונות מעשית) had its good qualities too. Altneuland offered a detailed idea of how the Jewish State would look and operate like and the possible problems it might face. It was progressive and liberal as well as nationalist, forwarding a plan for a democratic and inclusive state. It was also activist, and Herzl worked toward making this state a reality with various meetings with powerful heads of state and campaigned to gain support. However, the mere material focus for the establishment of Israel as a political fact overlooked the necessity of creating a nation. Here, the Hebrew essayist Ahad Ha’am got it right.

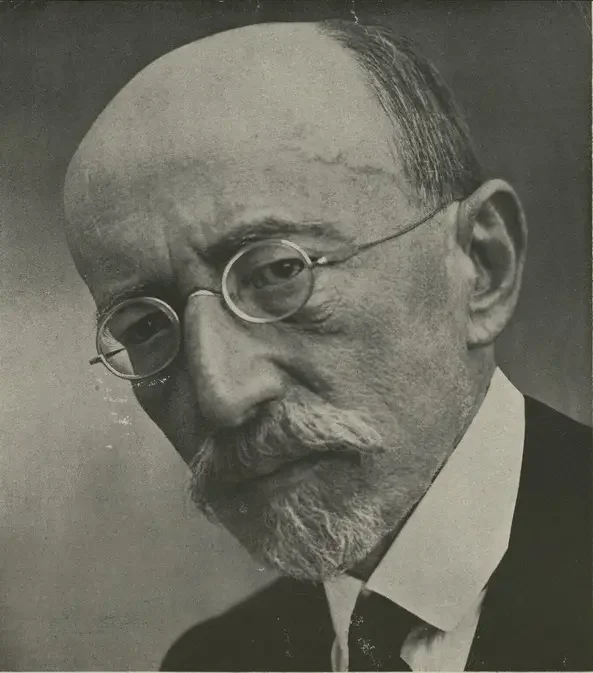

Ahad Ha’am אחד העם

Ha’am wrote The Spiritual Revival in 1902. It is an essay in which he criticises the practical and pragmatic Zionists for their dismissal of the need to resurrect the Hebrews as a nation and their misunderstanding of the question of culture. The question of culture was central to much of what Ha’am wrote and that’s why his strain of Zionism is known as cultural Zionism or ציונות רוחנית. I am not a fan of this translation since in Hebrew, the adjective רוחני is derived from the noun רוח which translates to “spirit”. This spiritualism I believe is deeper than that of culture, which although necessary to talk about, it is a product of this deeper spirituality and so the description of the ideas should carry this radicalism. Also, cultural Zionism has negative connotations with me given the rise of “cultural” Marxism.

Spiritual Zionism and the Linguistic Nation

What I noticed about the Spiritual Revival and what it got right in particular is Ha’am’s emphasis on culture being a necessary spiritual component to constructing a nation. In the case of the Hebrew nation, Ha’am references the need to preserve and develop Hebrew literature. He makes the claim (absolutely correct in my view) that language what makes a nation real. That is that Hebrew literature, in order to be correctly national, must be written in Hebrew and only then can it be truly part of a nation.

Ha’am writes on the necessary inclusivity of language and nation:

“Our “national literature” is often taken in a wide sense, to include everything has been or is written by men of Jewish race in any language. If we accept that definition, we cannot complain of the poverty of this literature. Heine’s love-poems, Börne’s crusade against political reaction in Germany, Brandes’ critical essays on all the literature in the world except the Hebrew – all these are ours, are parts of our national literature. But this conception is fundamentally wrong. The national literature of any nation is only that which is written in its own national language. When an individual member of that nation writes in a foreign language, what he writes may, indeed, reveal traces of his own national spirit, even if his subject has no connection with nation; it may even influence the history of his nation, if it deals with questions affecting their life. But national literature is not: it belongs wholly to the general body of literature of that nation in whose language is written…

…There is not a single language, alive or dead, of which we can say that it existed before its national language… before its national self-consciousness was fully developed – that language which has accompanied it through every period of its career, and is inextricably bound up with all its memories……Such is the strength of the natural, organic link between a human being and his own language. There is the same link between a nation and its real national language.”

And more specifically on Hebrew:

“…Hebrew has been our languages ever since we came into existence; and Hebrew alone is linked to us inseparably and eternally as part of our being. We are justified in concluding that Hebrew has been, is, and will always be our national language…”

What Ha’am touches on here is the essence of what I have been trying to explain for a long time (to myself as well as to others). The most important observation here is to me that language is essential to being. That national being is linked completely and utterly to the capacity for your language, that without your language you are but an empty shell and the foundation of your soul is lost. It is also important to note that Ha’am makes this reference in relation to a human being as a universalist concept, and not a nation. In this way, individualism is required for the nation to exist and vice-versa. The language gives us the first person plural which the late Sir Roger Scruton emphasised.

Worthy of note is the idea of the organicism between language and the being. Language’s existence is completely natural; it is, in other words, part of God’s plan, since that is reality and nature. That which is organic is true and not to be covered up by delusion and denial, but to be accepted to avoid conflict. Acquisition of self-knowledge is much the same process of giving into the reality of who you are and accepting nature. This must be done in the same way with language. The truth, nature and reality of who you are, your culture and history, follows binding connection to the natural historical development of any given language. And that link is also present between you and the nation. This means that the nation is deeply spiritual as opposed to the state which is material. Both, of course are essential, since without a state you couldn’t maintain a nation effectively, but without a nation, you have nothing special or meaningful. Ha’am also makes this point:

“It is, indeed, impossible to maintain that the material settlement has no bearing on our spiritual problem, or that this problem can be solved without the aid of such a settlement. On the contrary, the whole point of the material settlement consists, to my mind, in this… that it can be the foundation of that national spiritual centre which is destined to be created in our ancestral country.”

The movement for Zionism, and in this particular case the spiritual movement, is what must be adapted for a universalist audience. The idea of the linguistic connection in regards this spiritualism and the necessity to construct a national literature is what democratic nationalism should be all about. The problems of the modern society illness, the meaninglessness of social nihilism where all genuine spirituality has been pushed out by commercial nonsense are in need of a cure. Reconstructing that sense of meaning and responsibility through the regeneration of our European nations is calling for Humanity. The story of the Jews and Zionism is a real world story for what we must do. The Jews are representative of every people and their search for national self-determination and spiritual development. This is why Hatikvah turns into Tikvah Universalit.