From Russia with Destabilization

Superfluous though it might be to begin an essay with a poem, the situation in Ukraine merits an emotive prologue. And there’s something in Ukraine’s national poet Taras Shevchenko’s Testament that eulogizes and echoes the centuries-old anti-imperialist struggle that Ukrainians have been forced to conduct their entire existence; ecce:

When I am dead, bury me

In my beloved Ukraine,

My tomb upon a grave mound high

Amid the spreading plain,

So that the fields, the boundless steppes,

The Dnieper’s plunging shore

My eyes could see, my ears could hear

The mighty river roar.

When from Ukraine the Dnieper bears

Into the deep blue sea

The blood of foes… then will I leave

These hills and fertile fields--

I’ll leave them all and fly away

To the abode of God,

And then I’ll pray…. But until that day

I know nothing of God.

Oh bury me, then rise ye up

And break your heavy chains

And water with the tyrants’ blood

The freedom you have gained.

And in the great new family,

The family of the free,

With softly spoken, kindly word

Remember also me

Albeit an English translation, the linguistic is an appropriate way to start any prose concerning Ukraine, since the Ukrainian language – as the genesis of its culture and national character – is such a crucial target for the Russian aggression since it represents a sensitive theme of Ukraine’s own self-determining fight, like any language does to any national movement. Ahad Ha’am, the theorist of spiritual Zionism, and himself both native to Kyiv and a resident of Odesa under the Tsarist Empire, wrote “such is the strength of the natural, organic link between a human being and his own language. There is the same link between a nation and its real language.” Though speaking on the importance of a Hebrew revival, Ha’am’s aphorism here represents something of a maxim; Ukraine’s droite d’être rests in its continued existence as a language. And Shevchenko, as the nation’s poet, represents that for the Dnieperian country…

You’ve Never Been Right Before, Why Start Now?

More than two million Ukrainians have already found themselves displaced due to the atrocious Russian aggression. Millions more are likely to follow as Kyiv is constricted and Mauripol pulverized, and the most infuriating part is how pointless this entire war is. What was once avoidable from 2014 right up until the day of the invasion, the humanitarian emergency is now becoming more defined, and there’s no particular reason for it besides the hellbent pursuit of Russian irredentism for the restoration of the lost Tsardom. Putin has not only threatened ordinary Ukrainians by turning their lives upside down, but his reprehensible flirtation with nuclear warfare reminisces the euphonious Cold War surrealism.

I must admit, like many others (though notably not the White House), I did not believe that there would be an invasion of Ukraine – and certainly not in the flagrant barbarism of a full-on military takeover; I was convinced it would be an army-backed coup and nothing more. But as soon as the first simmering of a possible invasion started, I did know what I expected to infect social media. Russia – especially under the Putinist junta – has long been given controversial appraisal by many so-proclaimed “dissident” political commentators in the West, so I knew I was in for aggravation. And it’s become apparent that most of the pro-Kremlin apologist rot was already waiting for a chance to splurge across the Internet. On a personal level, it’s been revealing to see so many that I regarded as allies during the democratic-populist revolutions of the late 2010s, descend into gibbering hysteria over the alleged West provocation of this war; to watch Maajid Nawaz’s fall into hysterical paranoia over both the COVID-19 mandates and this war has been especially harrowing.

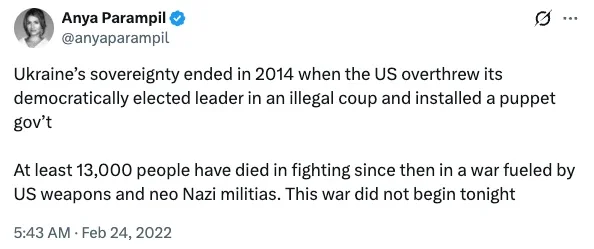

The misconception that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine originates from a realist geopolitical response to NATO expansionism has now mutated into a trope, and many political scientists, international studies academics, and journalists (people who should know better) argue it passionately as the root cause. This trope has been permitted to coagulate into both explanation and most callous justification for the aggression against Ukraine and her citizens by its ex-imperial vozhd. That it was pressure from Washington that pushed Ukraine out of some fanciful “neutrality” in 2014 and thereby prompted a violent and hostile Russian reaction. In one of the nastier – and more blatant – tweets I came across, this entire case is summarized almost periodically:

See original Tweet: https://x.com/anyaparampil/status/1496707383556513792

Quite possibly unbeknownst to Ms Parampil but, sensitive to dejà vu as I am, I have seen this exact case presented time and time again, and each time verbatim. And although my expectation for the so-called “anti-war” journalists is not high when it comes to critical thinking, the ignorance behind this case has spread pandemically. I have been hearing this argument from both right and left-wing writers alike, and it’s certainly not an old one. Like they tried to play down the extent of the Bosnian Genocide in 1994 or the attempt to trivialize the Taliban in 2021, it is unsurprising to see them yet again on the wrong side of history, apologising for this vicious form of Russian jingoism

I think one of the consequences of holding Western-style democratic nations to almost unattainable standards of conduct (and decidedly doing the opposite for anything anti-Western), is you will find yourself blaming the West almost exclusively, and defending some of the most rancid dictatorships and human rights abuses. Not only, but you will also find yourself giving way to lazy, sloganic analysis, parroted from some pundit, and feeling entitled to an unearned badge of “free-thinking”; in short, it is a lot easier to say NATO and the West are culpable than delving into the details that might challenge your view. This is not to say you should not hold the United States accountable for its support of the Honduran Coup in 2009 or consider any of its other crimes throughout this and the previous century. It is simply saying that if you are an anti-imperialist, you must be opposed to all imperialism and not try and get out of it with some Whitlamian sleight of hand.

Destabilizing an Unstable Country

Ms Parampil does have one thing right (stopped clocks and all that): Ukraine did not lose her sovereignty in 2022. But neither did she lose it in 2014 when Russia annexed Crimea and encroached on her territory. The reality is that for most of her independence, Ukraine has consistently had her sovereignty violated by its neighbor, and been the victim of both extortionist economic policy and meddling in its political processes, despite guarantees for her security given in the Budapest Memorandum in 1994.

I do find it incredulous when certain academics and pundits suggest that Ukraine was in a neutral state from 1991 onwards. It marks a serious flaw in the so-called realist perspective of international affairs that constantly disregards the importance of closed-doored, covert interference. It also reveals it to be very much fantastic and utopian. To believe that a regime such as Putin’s, that doesn’t even allow Russians to interfere in their own affairs and with a track record of trying to influence both elections and perspectives through disinformation campaigns, would allow its most coveted neighbor to make her own decisions, is to engage in delusion. And while this inference is often obscure and thereby overlooked, it is a critical part of understanding why Ukraine’s destabilization in 2014 was due to Russian meddling, and not NATO’s.

Indeed, the idea that it has been NATO provocation that has made Russia hostile, and not the notable shift in policy with the Putin presidency, is ahistorical. Long before the Bucharest Summit that rejected inviting Georgia and Ukraine to join NATO, Russia had already been slowly destabilising both countries. In Ukraine’s 2004 presidential elections, the opposition candidate, pro-Western Viktor Yushchenko, was “mysteriously” poisoned with dioxin. While it is certainly likely that Ukrainian authorities ordered the poisoning, it is dubious that they would have done it without the expressed go-ahead from the Kremlin. It would be odd that a weapon so conventionally Russian in both its Soviet and post-Soviet era, would be used sporadically by a Ukrainian establishment. The subsequent fraudulent election of the pro-Russian candidate (and incumbent prime minister), the corrupt slime Viktor Yanukovych, would have served the Putinist interests if Ukrainians hadn’t revolted to overturn the crooked result in the Orange Revolution. A Ukrainian friend once quipped while I complained about the efforts to overturn the Brexit vote, “at least you don’t have to have a revolution after every election”. The 2004 presidential elections were run again and Yushchenko was confirmed as president, much to the distaste of the Kremlin.

If Yushchenko has been more successful as a president, Ukraine’s internal politics might not have been so socially unstable come 2013. If Yushchenko had tried harder to compromise on genuine issues for Eastern and Southern Ukrainians, worked harder at ensuring national unity, and even considered Russian as an official language, he probably would have won again in 2010. However, his disappointing deterioration led to his demise, and to former prime minister Yulia Tymoshenko’s ascension as the leading pro-West candidate. Tymoshenko’s narrow defeat in the 2010 elections to a resurgent Yanukovych would have possibly been avoidable too. Yanukovych’s victory in 2010 was – I concede with the international consensus – likely to be a legitimate win, though not totally free from all fraud. Certainly, there was much change in Yanukovych’s stance in his second run for the presidency. Opportunism is as snake-like as it is slimy, and it appears he softened his pro-Russianism to take advantage of a politically weak Tymoshenko Bloc; it does also seem clear that many of his so-called base were, in fact, voting against Tymoshenko rather than for him. Nevertheless, Yanukovych lost no time in imprisoning Tymoshenko, as still a potentially formidable political opponent, for politically motivated corruption charges, and embarked on his power grab with heightened authoritarianism, particularly against press freedom.

Despite Yanukovych’s obvious preference for closer ties with Russia – his first language is the Russian of his hometown Donetsk where he served as governor – there was a considerable amount of effort on his part to placate the inherent instability in Ukraine. Maybe he understood out of some cowardly virtue, the reaction of the pro-Western Ukrainians from the Orange Revolution and consciously set out on a supposedly “neutral” approach. Yanukovych did pursue both a pro-EU line while trying to improve relations with Russia, and in 2010 he immediately signed the Kharkiv Pact with the Russian Federation to negotiate a cheaper gas price for an extended lease for continued Russian naval use of Sevastopol until 2049. And in 2012, Yanukovych signed the EU-Ukraine Association Agreement to begin Ukraine’s accession to the European Union.

What began happening in the August of 2013 – just months before the Euromaidan protests began – was I think the inchoative turning point for Ukraine’s destabilization. In violation of both the Budapest Memorandum and the Kharkiv Pact, the Russian Federation initiated a trade war against Ukraine for no particular reason, other than the fact Ukraine had resisted other more “diplomatic threats” to cease from EU accession. Starting with a ban on the import of Ukrainian chocolate (particularly from president-to-be Petro Poroshenko’s Roshin brand), Russia moved to change its customs and trade regulations that essentially stalled Ukraine’s industrial production output, dropping 5% each month following August. The gas price discount negotiated in the Kharkiv Pact had almost doubled from the agreed-upon price.

In late 2013, when the rumblings of the Euromaidan were beginning, Moscow invited Yanukovych for talks regarding the situation. All that can be known about the talks is that there were six rounds (the last being only one I could find dates for) and that, in true mafia style mnemonic of the government he was running, Putin either threatened or seduced Yanukovych into a “generous” $15 billion package to bail Ukraine out of a crisis that he himself had instigated. Although it’s much more likely to have been a threat, as some sources suggest a brutal ultimatum to “crush Ukraine” from the Russian president to Yanukovych, there’s every indication that he was also wined and dined for his seduction. Certainly, he was flown into Moscow on the private jet of a well-known Ukrainian oligarch Rinat Akhmetov – himself a Russian stooge and mafia implicado, so the possibility of either force or lure, or both, is evidenced for. In any event, the cajoled Yanukovych announced the stalling of the EU Association Agreement for the Russian bailout; this was the ultimate trigger for the Euromaidan revolution.

After Ukraine was destabilized with the Revolution of Dignity in the February of 2014, and after Yanukovych had fled Kyiv to you-know-where, the pro-Russian protests in the East Ukraine at what was regarded as a pro-Western revolution of a democratically elected president, flared up. Indeed, anger was completely reasonable as a country only held together by the democratic compromise on both sides is a delicate thing that should not be meddled with. But Russia did it anyway, feeding the separatist movements in Donbas and leading Ukraine into a proto-civil war. Either deliberate or stupid, it’s beyond doubt that it was Russia’s actions that prompted the destabilization of Ukraine in 2014, and not NATO expansionism with some feeble unwise interventions of late US senator John McCain. An important point here also is that, in 2014, Eastern and Southern Ukrainians never supported Russian intervention on Ukrainian territory.

Actually, It’s Russia Who Doesn’t Understand Us

The notion that Ukraine, an independent nation recognized at the UN, a member of the Council of Europe, and a founding member of the Commonwealth of Independent States, should be expected to forgo her sovereignty to placate the feelings of a fascistic junta in Moscow is a disgrace to both democratic and international politics. That Russia is somehow entitled to some sacrosanct “sphere of influence” is such an outrageous suggestion that it would only be acceptable to out-of-touch academics. Indeed, no power, great or small, has such a right to such international influence without earning it. But for some clandestine reason, the consensus of optionality over Ukraine’s existence has become some kind of conventional knowledge, yet this proposal for Ukraine’s pseudo-independence is so incompatible with the way that international politics is conducted in the post-Cold War era. Due to its antiquated and imperialistic approach to its foreign policy, the Russian establishment has risked the diplomatic relations of both allies and potential allies alike. Not only is the regime entirely responsible for its pariahdom and poor relations with the West, but it can’t even be decent enough to wipe the neocolonialist dribble off its chin in the company of friends.

Despite the apparent obsequious attitude of the cretinous Belarusian dictator Lukashenko, there have been near Tito-esque strains in the relationship due purely to Russian nostalgic hegemonism. Over the appalling invasion of Georgia in 2008, where (unlike NATO in Kosovo) Russia invaded on the side of ethnic cleansing and genocide in support of the separatist regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia, the Russian regime offered Belarus a $500 million bribe on the condition Lukashenko would recognize the breakaways. The Belarusian refusal led to Russian banning milk imports from Belarus and consequent Milk War and, since the Russian military intervention in Ukraine in 2014, Lukashenko has pursued a more pro-Belarus cultural and linguistic revival. Russian imperialist ambition is exclusively to blame for stoking the flames between the only two members of the “Union State”. Putin has also managed to piss off a long-standing ally in Kazakhstan by claiming in 2013 “the Kazakhs had never had statehood”, leading the country to threaten withdrawal from the Eurasian Economic Union

Perhaps the most flagrant and pernicious aggression (until Ukraine) has been the invasion of the Republic of Georgia in 2008, not only on the side of genocide but also creating a practically irreversible frozen conflict denying Georgia’s ability to pursue an independent foreign policy effectively. There’s plenty of evidence to suggest that the conflict came out of the Putinist ascension to the Russian presidency, noting the 2002 handing out of Russian passports to unrecognized Abkhaz citizens, and the 2006 Nuremberg-like purge of ethnic Georgians from Russia following the expulsion of four Russian spies from the Caucasian republic. The 2007 shelling of the Georgian administrative building by a Russian helicopter and continued supply of arms to the separatists stoked the flames for a conflict the following year. In tactics scarily reminiscent of the war against Ukraine, Russia recognized the independence of Abkhazia and South Ossetia and proceeded to invade Georgia, occupying the territory ever since. This prompted Georgia to withdraw both from CIS and also any potential alliance Russia and Georgia could have developed if it wasn’t for the latter’s revanchism. All this was started before the Rose Revolution in 2003, and even longer before the Kosovo declaration of independence in February 2008 as well as before the NATO Bucharest Summit in April.

It is also worth pointing out the way Putin has ridiculed and embarrassed his “own” country and people, to add Russians to the long list of “friends” he had managed to vex. The Russian shame over the doping scandal in sports and the theft of their elections should be a point of grievance of the Russian people against their own government that claims to act in their interests. I don’t believe that many Russians appreciate how he has upset relations with the West, either by interfering in elections or carrying extrajudicial executions on foreign territory or by inducing more sanctions by his irate actions.

Ahh, But Kosovo!

The idea that NATO has either been aggressive or threatening towards Russia since the collapse of the Soviet Union does appear to me to be completely fictitious. The rather dubious claim of “security concerns” doesn’t hold much water either, since NATO-Russian relations, although never warm, have been coldly cordial over many issues. In fact, it was only in 2014 with Russia’s unilateralism over the annexation of Crimea and its military intervention in Donbas that paralysed the military cooperation that the two had undertaken since 1991. And it is also worth pointing out that Russia is still a member of the NATO Partnership for Peace, despite being the main antagonist to it. Russia has needlessly and dangerously made an enemy of NATO for nothing more than to serve as a distraction to its own domestic woes.

Now the claim that NATO is purely a defensive alliance is not easy to defend, it is true. But it isn’t easy to argue it’s an offensive one, either. In fact, I think you would be hard-pressed to find a war involving NATO that wasn’t aimed at ending violence. I myself can only think of one particularly aggressive act in 2001 when NATO invaded and occupied Afghanistan, and this was of course a response to the 9/11 attacks whereby the US triggered Article 5 of the treaty. The other possible example might be the imposition of a no-fly zone over Libya in 2011, whose actions – although backed by a UN resolution and justifiable in the light of the Gaddafi regime – had rather questionable motivations involving French interests. In my view, the Libyan intervention was more of an international failure than a violent adventure

Many commentators turn to NATO’s bombing of Yugoslavia in 1999 against Serbian national socialist Milosevic’s grotesque drive for a Greater Serbia as the key turning point in NATO-Russian relations. Of course, there is truth that Russia since 1991 had found itself in a greatly weakened position on the international stage and took NATO’s perceived unilateralism as insensitive, but it doesn’t then follow that Russia necessarily had to take the wrong side in that war. The actual reality for Russian resentment towards the West began with the failings of Boris Yeltsin’s liberal reformism. By 1998, the Russian economy was in freefall with the ruble in tatters, and Yeltsin found himself forced by the Russian Duma to appoint hardliner (though pragmatic) Yevgeny Primakov as prime minister. When NATO’s intervention in Kosovo began to play out in March of 1999, Russians were almost exclusively exposed to reproduced Serbian propaganda in Russian media that fanned the blazes of anti-Western outrage over the intervention. Yeltsin, in a last-ditch attempt to save his presidency, unwisely utilized the conflict as a distraction for short-termist gains. Obviously, this failed and only deepened the mistrust of the West and led to the appointment of Vladimir Putin.

I do think that some of the Russian sympathisants have a point in regards to Western culpability over Russia’s demise as democracy, but only up to a certain degree. Among the many mistakes, Yeltsin made, trusting that glib egomaniac Bill Clinton was probably one of the more damaging, as America’s indifference towards Russia’s exponential cronyism and corruption was probably more of Clinton’s aspiration for his own country than of his concerns for Russia. Unfortunate though the state of the US was at the time for welcoming Russia into the fold, ultimately the domestic politics of Russia were directly responsible for the chilling relationship. Since Putin’s rule began, the deliberate misunderstanding over the so-called “assurances” given by NATO to Gorbachev’s USSR has become twisted into a stab in the back myth to illustrate this sinister trope of “national humiliation”, allowing him to create his pan-Eurasian fascist state with Duginist inflections.

Fighting for a Democratic Ukraine

I will not make the grave mistake of arguing that Ukraine is an exemplary democratic country, and I doubt many Ukrainians believe this either. Either by fate of constant outside meddling or by the plague of corruption after the Soviet era, Ukraine has struggled to establish itself as a country based on the rule of law and democratic standards, a struggle that has required a significant fight and sacrifice from its people. That being said, Ukraine has undoubtedly been more successful in its post-Cold War liberalization than either of its neighbors and it’s likely that has been a core part of the antagonism.

A popular objection floated by those desperate to oppose the opposition to the war in Ukraine has been to highlight the presence of Ukraine’s Neo-Nazism. It’s been interesting to see so many commentators who try so hard not to see Nazis, who constantly tell us their influence is overblown and will shut down discussion about anything far-right as hysteria, be so ardently indignant about Ukraine’s ultranationalist movements. Not only is it interesting, it’s suspect as many of these characters appear only to have found out about these groups recently; I’m thoroughly convinced Maajid Nawaz only discovered them two days after the invasion started. I am just as unconvinced by those who point out these the Ukrainian Neo-Nazis while lauding the action and ideology of terrorist groups like Hezbollah.

It is true, however, that Ukraine’s far-right has played a part in both the Donbas War and in the violence preceding the Revolution of Dignity that ousted Yanukovych. In early 2014, the far-right group the Right Sector organized the street riots that led to clashes between police and protesters. They were also caught handing out translated copies of Mein Kampf and the Protocols of the Elders of Zion to protesters in Independence Square. After the revolution and Yanukovych’s flight from Kyiv, the far-right Svoboda party took part in the new coalition under the new Poroshenko presidency – a worrying choice that had all the hallmarks of being out of incompetence and naivete (particularly from the American handling of the situation). Another stupid decision by the Poroshenko government – is supposedly an attempt to deradicalize and normalize some of the Neo-Nazi militias in Donbas – was to integrate the notorious Azov Batallion into the National Guard. Again, commentators enjoy underlining the point that the US has been funding this group, but fail to mention the US Congress blocked any funding to Azov from 2018. Ukraine’s Neo-Nazi problem, though indeed present and worrying, doesn’t have electoral support that many some of these commentators would like. Even at the height of its influence in 2014, Svoboda only had six seats in the Verkhovna Rada, losing five of them in the following parliamentary elections. Even so, when the war is over, I expect to see all Neo-Nazi paramilitary groups on trial for war crimes.

I am no fan of Mr. Zelensky. I don’t believe the situation in Donbas has improved under his presidency nor do I like the authoritarian tilt his government has taken under his sweeping anti-corruption measures; his repression of the media is reminiscent of Yanukovych’s crackdown before Euromaidan. Zelensky’s conduct over the invasion has also led to him making very problematic decisions, such as giving arms to anyone who’ll take them, as well as releasing prisoners to fight for Ukraine. Not to mention the ridiculous requests to fast-track both EU and NATO membership that were also going to be rejected. But the main reason I lost patience with Zelensky was over the suggestion of NATO imposing a no-fly zone over Ukraine seemingly unaware of the catastrophic consequences that would have. However, Zelensky has cut a strong figure on the world’s stage and the very least you can admit is that he has remained in his country to continue the fight. This is much more than can be said of other former presidents such as Ben Ali and of course Yanukovych. Under Zelensky’s leadership, Ukraine’s morale appears to have remained high despite the odds and I think credit where credit is due.

There is a democratic Ukraine we should be on the side of, and we must consciously give our support for that movement in the country. This is a proxy war, in many ways, between fascistic dictatorship on one side, and democracy on the other. As democrats and believers in a democratic Ukraine, we should be in support for a Ukraine that exemplifies the best qualities of the rule of law, civil rights, and separations of power. And we must oppose the ethnic sectarianism and imperialist fascism coming from either the Neo-Nazis within Ukraine or the Putinist junta. There’s not much for NATO to do other than ensure the Ukrainians win this war and unfortunately it will have to be the sacrifice of brave Ukrainian fighters to secure the victory. But if victorious, and Putin falls, then the West can have another opportunity to give both nations what we should have helped them develop over three decades ago.